|

© ENJA RECORDS

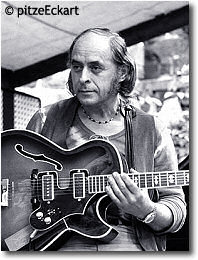

Attila Zoller was a great guitar player, not so famous but

almost discovered after his death. His most remarkable colleagues like Jim Hall, Pat Metheny,

John Abercrombie, John Scofield, Mike Stern...recognized him as one of the

best of them. Attila Zoller met Bill Donaldson on 9th January 1998,

few days before his death which was on 25th January because a cancer. This

is the last Attila interview, he was aware about his health state, he was

constrained to assume morfine, but he was available to tell his story, to

transmit his love for music. Thanks to Bill

Donaldson and Cadence Jazz Magazine, for giving us the authorization

to publish this long interview to a great musician like Zoller. So long Attila!

Marco Losavio |

CAD:

I understand that you were born on June 13,

1927.

AZ:

June 13, yes, in Visegrad (Hungary).

CAD:

Was your family musical?

AZ:

Yeah, my father was. I mean, my whole family was musical. My sister was playing violin. My mother was not; she played piano a little and she sang. My father was a professional teacher. He was going to be a concert violinist. But he was not out playing concerts. That was his goal. Anyway, we lived in the town outside Budapest, and so he was teaching.

CAD:

Where did he teach?

AZ:

In the conservatory in Budapest before the war. He started me on violin when I was four, and later I played trumpet when I was nine or ten already. I played trumpet in the high school orchestra until I was 17. I just picked up the trumpet, and afterwards I took lessons. When I went to the first high school class, I joined the orchestra there.

CAD:

What type of music did you play then?

AZ:

Bartok and Kodaly music - you know, Hungarian things.

CAD:

Did you start to play guitar after high school?

AZ:

After the war. During the war I played trumpet still.

CAD:

When did you graduate from high school?

AZ:

The war finished the high school for me in

1945. Then I went to Budapest and started to work. It was all a mess at that time in Hungary, you know.

CAD:

How were the war conditions in Hungary?

AZ:

Well, in the last few months, the soldiers were in there. The Germans took over, and then the Russians took over. And that was quite a mess then.

CAD:

How did that affect you?

AZ:

Well, I mean, I was in my hometown, Visegrad, and had to survive.

CAD:

You continued to go to high school as long as you could?

AZ:

No, that was hard. In November, they sent us home and we couldn't go to the school. And the next year in May, we went for the first time to Budapest. There were five months when I didn't go to school. I mean, that was a bad time, you know. The soldiers just came in. I just started to play then guitar because the soldiers were there. Some of them got drunk, you know. If there is a church, that is fine, you know. So I was next to the church.

CAD:

Did you play in the church or did you play for the soldiers outside the church?

AZ:

Yes, I played a lot inside the church. I grew up in the church. I was living right next door to the church. I mean, in the town on the church square there was our house there.

CAD:

Did you play guitar to entertain the soldiers?

AZ:

Yeah. They came, and they were playing and I was playing. Some of them played accordion, and then we played accordion and guitar. I just figured out the chords, you know. I could hear chords. With my ear, I could put chords to tunes that I knew. It's not normal; you learn that.

CAD:

Were they German or Russian soldiers?

AZ:

They were Russian. The Germans were there before them. But I learned to play guitar when the Russians came.

CAD:

Was there any violence? CAD:

Was there any violence?

AZ:

Oh, a little violence, but not too much. There was some raping - soldiers going around to find a woman, you know. They would take what possessions they wanted. With my Jazz career, I had nothing to do. I went to Budapest; I played there in a band later. In a few months through another accordion player with whom I played in Visegrad, I met the top accordion player in Budapest.

CAD:

Tabanyi Pinoccio?

AZ:

Yes! How do you know Tabanyi?

CAD:

Was anyone else in the band?

AZ:

Yeah, a bass was in the band too and sometimes piano. And a clarinet player, he played too. But basically it was an accordion, bass and guitar trio.

CAD:

Where did you play?

AZ:

In restaurants, you know. With those engagements, you played every night for months. In

'46, I started to be more known in Budapest. In the summer of

1946 or

'47, we went down to the Balaton - a big lake. In the summers you went there for an engagement like you go to the Catskills. They're like the Balaton there. It is a big lake; you don't see the other side. That was just a simple engagement. That's unimportant. Ask me something important.

CAD:

Oh, but it is important. When did you go to Vienna?

AZ:

In '48, I went to Vienna. There I started to get interested in Jazz.

CAD:

Was that with Vera Auer?

AZ:

Yes. I met Vera Auer in Vienna in the variety show. I played bass in the pit. I played also double bass. Vera played accordion. That's how I got in an accordion bag. (Laughs)

CAD:

How did you meet her?

AZ:

It's some other funny story, how I met her then. This guy was getting from Hohner a special accordion made. It was Tabanyi, who was in Hungary. And it was stolen at the end of

'47 or the beginning of

'48. And I'm going to Vienna and this woman on the stage played Bach and this rhapsody - you know, classical music on the accordion. It was like an orchestra. And I see the accordion was the same accordion - the same number on it - which Tabanyi had. I thought somebody stole it in Budapest and brought it up to Vienna. I said, "Where did you get this accordion?" I went to her dressing room. And that's how we met altogether. I told her the story that I wanted Tabanyi's accordion, and she said, "Oh, you know Tabanyi!" I said, "Yeah, I worked a year with him." She said, "Oh, he's my big idol!" and all this shit. And we got together and she was interested to play Jazz, you know. I mean, that was not how Tabanyi played. OK, so I knew all his licks for a whole year.

CAD:

Where did Vera hear Jazz?

AZ:

She heard all the different Jazz bands. She always wanted to play Jazz. And then we got together and we started a trio again with me on guitar. She was very good in business, so she could get a lot of gigs. We played then in American clubs. We put a bass together and then the piano also and drums. I stayed with her until

'53. We played in Vienna mostly. We went to Istanbul in Turkey for three months in

'51. Hers was the first group that I had something to do with Jazz. Joe Zawinul played with us, you know.

He was our piano player later, and we had Hans Solomon on alto and clarinet. We played then

George Shearing-style things, and we did also some swing stuff. And then we played some

Tristano music - you know, a couple things what we heard from the records. That was the beginning, you know. When I first heard the

King Cole trio with Oscar Moore and Slam Stewart.... That record I heard in Budapest already. But really the first Jazz I heard was in Vienna. I heard the Tristano music, you know, and I later heard

Mulligan. Then when I came to the U.S., I heard Clifford Brown and Max Roach. They turned me completely around from the cool Jazz. Musically, it was not good - that cool Jazz. But Lee Konitz' sound, it sticks with me. And Lee Konitz was my idol improvisation-wise. In '55 we met in Cologne, Germany. And when I came over here, he was my friend. I went to his home, you know, to see what a nice family he had. Now he got remarried and lives in Germany. He was divorced for a long time, and then his second wife died. Anyway, we've been friends ever since, and we've been recording also in between. In '68, we had a record; it was called

Zo-Ko-Ma. It was an MPS record. I played the world around everywhere later. Later, we were with Tony Scott; I started to play with him in '58. When I played in Tony Scott's group, I had the chance to play with Bill Evans, you know, and

Jimmy Garrison and Pete LaRoca. Bill Evans was part of Tony's group. That was when

Scott LaFaro came in Monday afternoon for one of our rehearsals. And then he sat in there with Bill. Yeah, it was nice. And then later with Chico Hamilton I played, and Herbie Mann. He was our piano player later, and we had Hans Solomon on alto and clarinet. We played then

George Shearing-style things, and we did also some swing stuff. And then we played some

Tristano music - you know, a couple things what we heard from the records. That was the beginning, you know. When I first heard the

King Cole trio with Oscar Moore and Slam Stewart.... That record I heard in Budapest already. But really the first Jazz I heard was in Vienna. I heard the Tristano music, you know, and I later heard

Mulligan. Then when I came to the U.S., I heard Clifford Brown and Max Roach. They turned me completely around from the cool Jazz. Musically, it was not good - that cool Jazz. But Lee Konitz' sound, it sticks with me. And Lee Konitz was my idol improvisation-wise. In '55 we met in Cologne, Germany. And when I came over here, he was my friend. I went to his home, you know, to see what a nice family he had. Now he got remarried and lives in Germany. He was divorced for a long time, and then his second wife died. Anyway, we've been friends ever since, and we've been recording also in between. In '68, we had a record; it was called

Zo-Ko-Ma. It was an MPS record. I played the world around everywhere later. Later, we were with Tony Scott; I started to play with him in '58. When I played in Tony Scott's group, I had the chance to play with Bill Evans, you know, and

Jimmy Garrison and Pete LaRoca. Bill Evans was part of Tony's group. That was when

Scott LaFaro came in Monday afternoon for one of our rehearsals. And then he sat in there with Bill. Yeah, it was nice. And then later with Chico Hamilton I played, and Herbie Mann.

CAD:

Did you join Jutta Hipp after you left Vera Auer's group?

AZ:

That was in Frankfurt with Jutta then. I met Jutta when I went to Frankfurt, and we became friends. It was in that hillbilly club, you know. It was Nashville music in Frankfurt. They played things like "Steel Guitar Rag." (Laughs) That was the NCO club there, and there were mostly soldiers there. So it was good experience for me. Also, an accordion player played there who knew all the tunes and so on; I don't remember the accordion player's name any more. Jutta played piano. Later, I had to get some other engagements in between with other bands where I can make some money. So I went to Holland with a dance band, which was a good Jazz band actually. But they played their program for dance music. That was good; I made some money. That was not with Jutta then, however. After Holland, I went to Nuremburg. It was the end of a summer engagement in Holland, and that started for six months. We worked until March, you know. That was a great engagement. They paid three times the salary the other group paid. And after that, I went back to Jutta (in Nuremburg) because we had too many fights, you know. She was already in Germany a very established Jazz piano player. And it was like she was almost the only one on (Jazz) piano in Germany. There weren't a few good players; I mean, none played the caliber that she did. We played in Sweden and a few American club engagements in Frankfurt in '55. She came to the States in November of '55. And then I played in a Dutch band in France in different American clubs for soldiers who were stationed there. I finished with that Dutch band. Of course, I didn't work after that, and so I followed Jutta in January or February. That's why I came here in '56 - we were engaged and supposed to get married, you know. We broke up. With Jutta, I made some contacts.

CAD:

But that didn't lead to many jobs?

AZ:

No, I didn't stay. I was with Jutta then for two or three weeks here. She dropped out in 1960. A lot of people think she recorded with Stan Getz. That's a big mistake. She recorded with

Zoot Sims. I don't think Jutta ever recorded with Stan Getz, except for one tune. It was her record where Stan played one tune.

CAD:

What did she do after she dropped out?

AZ:

She took a job in some clothing store making alterations or something. She stitched pants, if you know what I mean. I never saw her working, but I know it was a tailor shop.

CAD:

Why did she stop playing?

AZ:

I don't know. Everybody tried to arrange interviews with her, but she doesn't say why. And then after we broke up, I went back to Europe right away to start with Hans Koller. I had a loft in Frankfurt already, so I thought I'd go back to Germany and make some money and come back (to the United States) again. A friend already had a telegram for me saying I could start with

Hans Koller the first of April. Hans Koller was a saxophone player who Jutta used to work with before she split. They started their own quintets, you know. It was a Tristano kind of a quintet with

Emil Mangelsdorff on alto saxophone and Joki Freund on tenor. They were at that time very good established German musicians. For the rest of the year, I played with Hans Koller in the Cologne area. Roland Kovacs was on piano,

Johnny Fisher was on bass and Rudi Sehring was on drums.

CAD:

Were you affected by the Hungarian revolution in 1956?

AZ:

Of course, the Russians came in with tanks and everything, but I was already out of the country by eight years.

CAD:

Was your family still in Hungary?

AZ:

My mother was still there. I never saw her again. I couldn't go back to Hungary at that time. The next time I went back to Hungary, that was in '66. My sister is still there.

CAD:

Was she there during the revolution?

AZ:

Yes, they were all there. Four weeks ago, we had a big celebration in Hungary.

CAD:

What is your sister's name?

AZ:

Forget it. It's a hard name. You don't know how to spell it; we do. You have to forgive me; I hate this kind of a thing (an interview). I hate to do this. I'm 70 years and over, OK? And I'm not starting my damned career, you know. And now you're coming with an interview. This is 30 years late.

CAD:

That's why I wanted to talk to you. You have more insight and experience than a 22-year-old musician would. I'd like to document what you have to say.

AZ:

I know.

CAD:

You sat in with Oscar Pettiford and other Americans in Europe.

AZ:

The second time I came to (the United States), I met Oscar here. And then he came on tour to Germany at the end of '58. In '58, I was in Hamburg, and Oscar said he would like to stay in Europe. So he said, "Is there any work here?" I said, "Sure. We always need a bass player." I mean,

Hans Koller would always have a bass player - a really good one, you know. And he was willing to play with us. We played then a few months, from October of '58 to February. In 1959 was when we made that record (Black Lion) in Vienna. That's when I had to play double bass on a couple of tunes. There was no bass player around. But we never thought that it was going to come out. I wouldn't have played bass then if I knew they would release this album. I don't like to be put down. Somebody said, "That guy has some nerve playing bass with Oscar Pettiford." I mean, it was just a helping out. I played the right notes. It was

Jimmy Pratt on drums at that time.

CAD:

You recorded with Oscar Pettiford the year before he died.

AZ:

He was a healthy man then. Yeah, but he died from a stupid car accident, you know. He didn't take care of himself then after that, just like I don't take care of myself now. He was in a car accident with Hans together, you know. They both came out with a big bandage on their heads. I didn't see them coming out of the hospital. I just had the idea that I should try to contact a hospital. When they didn't arrive in Vienna, I thought, "Shit, man. I'll ask at the hospital maybe." He was in the hospital at that time, and then I don't know. The accident looked very bad because O.P. had his eye hanging out. It just looked like that, though, because he was cut on his right eye. Around the eye somewhere he had an injury. It looked like his eye was just open with no skin on it. They fixed everything, you know. He looked normal in a couple of days.

CAD:

But he didn't take care of himself.

AZ:

And later, then we took care of him. Everything was fine, but he couldn't give up that vino. O.P. wanted to have wine always. He wouldn't take his medical advice from his doctor. He'd say, "Ah, come on! Ah, come on! Just one! One little glass." You don't feel pain, and then you just drink another one.

CAD:

You were in New York in 1958?

AZ:

Ah, yes, that was '58 already. That's when I played with Tony Scott out of town, of course - not in New York. We played in colleges too in Pittsburgh and Harrisburg - different concerts with Tony. I had one interesting gig that I played that was in the

Showplace over on Ninth Street, you know. That was with Bill Evans and Pete LaRoca and Jimmy Garrison. In '59, I was here the whole summer. When I came back here, I played also bass in an East Side club, the Rain Tree. This was a little bar with a duo.

Jean Cunningham had played piano there; she was Bradley's first wife. You know Bradley's, the club. And then I played bass there. I didn't have a union card yet, so I had to play in kind of a black market.

CAD:

Why did you decide to move to the States in '59?

AZ:

In '59? Because at that time I knew already that if I wanted to learn Jazz right, I had to be here. And then I got a scholarship to Lenox School (of Music). Jim Hall got me the scholarship. He taught there, you know. There were no guitar players.

CAD:

How long did you study at Lenox?

AZ:

I was there for two weeks, I guess. Then we were rooming together with Ornette Coleman and Don Cherry. We were the three oldest guys. There were not single rooms there; they always doubled up. They tripled us! It was a big room. At that time, we got into a lot of arguments about this stupid kind of a playing what he was trying to do - playing without changes, you know. And then after a couple days, I (stood) behind him. I put some psychology to it. But when somebody is into changes like I was at that time already, that was why I made it so fast in Austria and Germany. That's why I could play like that - because I had some ears. But I found out in between then that people don't have ears. Most of the people play the music how they know it, and that's how they play their machines. They don't feel the music. They don't play the music right. They don't know even what it says. Anyway, I'm not going to begrudge them because I never made it. It doesn't matter. I'm still making records. I'm too critical.

CAD:

Then you went with Chico Hamilton after you came to the States.

AZ:

Yeah. For me that was already after the Lenox thing. Chico was always probably asking around because he needed musicians for traveling, you know. And I was just the perfect cat because I had nothing and I could travel. I just got married at that time, and we didn't want her to stay on the road - my wife at that time. We have been divorced already for 30 years. I was just married for ten years.

CAD:

How did you meet Chico?

AZ:

Chico? Well, he called me. He was asking around. Someone recommended me. I guess he asked

Kenny (Burrell) probably. That was what he said. Anyway, that was for six months. And then he stayed there in New York. And then we formed a group with

Bobby Jaspar. He's a Belgian tenor player. It was very nice - with G.T. Hogan

and Eddie de Haas. That engagement was in the Vanguard.

CAD:

Was that recorded?

AZ:

No. I have recordings from that group, you know, but not in the Vanguard. We did some private recordings because we tried to make demos, you know. We went to Europe; we played in the festivals in '61.

CAD:

And you joined Herbie Mann after that.

AZ:

And then I came back, and this bossa nova thing started. Chuck Israel - he was my neighbor on that street - one day he came over and said, "Listen to this record here." It was Joao Gilberto singing. I said, "Nice. Nice commercial sound. Nice singer." But it wasn't Jazz, you know. Anyway, that groove caught on in a few months. Then Stan Getz came out with a big hit. And Herbie Mann played it. I stayed with him for three years at least. We went several times to the West Coast and Japan. He always had engagements (in New York). For 20 weeks a year, we played in the Village Gate alone. The Village Gate was where we lived!

CAD:

When did you meet Don Friedman?

AZ:

Ah, that was in between. We got Don into the band. I met Don in 1960 in the Five Spot when he played opposite Ornette Coleman. Don played that kind of a music I liked to hear in those days. Like Paul Bley. Already in the beginning, I said, "You're going to change the whole music scene, huh?" to Ornette, you know. No more Bachs. No more Mozarts. No Beethoven. No changes. Just blow, man. Blow what you feel. (Laughs) And then what is the bass player supposed to do? He's supposed to play some tune, huh? The drummer is all right because he has no pitch. They say, "Oh, just play close to the melody." That is what they said. What melody? (Laughs) "What do you play? Was there a tune?" To find out the melody, you have to find the right sounds. We got behind it. You know, it's not supposed to sound harmonious. But it's always melodious. They played always very nice melodies. You know, that's what I didn't understand. It came out so good always. Charlie Haden did a great job there too with them. I'm talking about the

Five Spot already when I saw Don there. And then I got together with Don at the Five Spot, and I heard his previous album,

Flashback (1963 Riverside). He was into that kind of music, so I said, "Let's try some originals." We started to rehearse, and Don had another date coming up. And we played

The Horizon Beyond

kind of music. I mean, my date was

The Horizon Beyond; that was the name of the album and also one of the tunes. But we played also free stuff with Don Friedman. He was writing free stuff. That's where the "Weather Report" name comes from. You know, I saw

Zawinul when he was with Cannonball. We've been friends since Vienna. I brought down my records that I made -

Cat and Mouse, The Horizon Beyond

(Emarcy) and what I had already recorded. And then he said, "Your band sounds like all these seascapes and blizzards and springtime." He said, "Your band sounds like a weather report…" (Laughs) "…Talking about the weather always." And then five months later his new group was named

Weather Report. (Laughs)

CAD:

Did you join Red Norvo and Benny Goodman after joining Don?

AZ:

Yes. Tal Farlow was an old friend of mine from a long time ago because in '58 when I was here I was every night in

The Composer where he was playing. He was my big hero. We used to hang out, and I would go home with them - you know, his wife. She was very nice - Tina. They invited me over. We used to play there early in the morning. It was a good lesson for me. Always he'd say, "How do you know these chords?" I'd say, "I'm looking at you." He'd say, "And you can get it right away?" I mean, at that time I'd look at him and that's how I learned. And for some nice voicings that he was doing, nobody can get the grip, including me because I have such big hands. Anyway, he's been a good friend of mine for a long time. He was writing with

Red Norvo. And Red came to town and needed a band in the Rainbow Grill, and (Farlow) asked me if I wanted to put a band together for Red. I said, "Sure." That's when I played with Red. Of course, Benny heard about it, and the next time Benny hired me. It was a good thing to do that because anybody who heard

The Horizon Beyond might have the idea that I couldn't swing. That's why I played with them - so that they lose that impression. If you play with Benny Goodman for more than one night, then you must be able to swing. I played in the

Rainbow Grill (with Benny Goodman) again. And then we went for a ten-day concert tour. There was a record date too, I remember - like Benny Goodman in Paris (1967 Command) or something like that. It had some French tunes that we were playing there:

Michel Legrand stuff and so on.

CAD:

After Benny Goodman, you had a group with Lee Konitz in it?

AZ:

In '68, we went on a tour to Germany. That was my tour. It had

Albert Mangelsdorff and Lee Konitz. I mean, Lee wanted to come. I said, "I can't take you to Europe as a sideman." "Why?" "Because you are Lee Konitz!" But we were friends already for many years. But he said, "Hey, I want to do this." He wanted to go to Europe, you know. We recorded an album called

Zo-Ko-Ma (MPS). "Ma" stands for "Mangelsdorff." Lee wanted to play free also, but he was not able to do free Jazz. I'd say, "You're not doing it the right way.

"He didn't have the picture of how it was supposed to play free. If I play with him, I want to play changes. And now he plays changes. He sounds great. For the last three or four years now, Lee is playing his ass off. (His playing) is so vital and much stronger...not that cool shit, you know. In '70, I recorded

Gypsy Cry (1969) on Embryo label. It was on Atlantic, actually, with the Herbie Mann production label. And they called that series "Embryo," which recorded about five other artists, including Ron Carter and

Arnie Lawrence. He had a whole bunch of them. (Mann) recorded musicians who used to work with him. He bought Miroslav Vitous' tape because he found out that some of the tapes had disappeared. So they bought the whole thing and just put it on a shelf. Herbie

Hancock played piano on

The Gypsy Cry. At that time, Herbie

Hancock was struggling. The drummer was

Sonny Brown, and now he's disappeared and I don't know where he is. Reggie Workman

was on bass. Also, Victor Gaskin was on too because I wanted two dates. It was two different kinds of music I played on the album. I played one part avant garde stuff and another part of popular stuff. The dates were on Tuesday and Thursday. The first date had standard type of styles, and the second had Hungarian folk-type motifs. They were all original compositions, of course, but I own that Hungarian style. We tacked on this free Jazz playing. We had started to do that. Ornette Coleman, you know, turned everybody on to this free type of playing. So anyway, we played that type of thing and regular Jazz. That's why I had two bass players. Reggie is better at the free stuff. "He didn't have the picture of how it was supposed to play free. If I play with him, I want to play changes. And now he plays changes. He sounds great. For the last three or four years now, Lee is playing his ass off. (His playing) is so vital and much stronger...not that cool shit, you know. In '70, I recorded

Gypsy Cry (1969) on Embryo label. It was on Atlantic, actually, with the Herbie Mann production label. And they called that series "Embryo," which recorded about five other artists, including Ron Carter and

Arnie Lawrence. He had a whole bunch of them. (Mann) recorded musicians who used to work with him. He bought Miroslav Vitous' tape because he found out that some of the tapes had disappeared. So they bought the whole thing and just put it on a shelf. Herbie

Hancock played piano on

The Gypsy Cry. At that time, Herbie

Hancock was struggling. The drummer was

Sonny Brown, and now he's disappeared and I don't know where he is. Reggie Workman

was on bass. Also, Victor Gaskin was on too because I wanted two dates. It was two different kinds of music I played on the album. I played one part avant garde stuff and another part of popular stuff. The dates were on Tuesday and Thursday. The first date had standard type of styles, and the second had Hungarian folk-type motifs. They were all original compositions, of course, but I own that Hungarian style. We tacked on this free Jazz playing. We had started to do that. Ornette Coleman, you know, turned everybody on to this free type of playing. So anyway, we played that type of thing and regular Jazz. That's why I had two bass players. Reggie is better at the free stuff.

CAD:

Was it tough in the 70s?

AZ:

Everybody was struggling in the 70s. The 70s were a hard decade, but I did try a few important things. One was playing solo. Nobody soloed on guitar and worked in a Jazz club. A lot of people play solo guitar, but in a Jazz club it was never yet an act like later what Joe Pass would do with solos. But I played the whole set solo at that time. I thought I started something, and then Joe Pass came out with his

Virtuoso albums. So I lost interest in that direction.

CAD:

Did you record a solo album then?

AZ:

Then I didn't. I just meant to make one at that time of solo pieces. I thought I had established a guitar style of "having your band with you in your head." (Laughs) And I tried to play that way and not trying to play the way Joe did, you know. That isn't everything. Some can learn the tunes and play the same way that they're written and everything. There is no interaction between the strings. You know what I mean? Each string has a voice to play. Ah, I don't think I should explain to you solo playing. That is already complex. After (Gypsy Cry) came out, then I saw that the record disappeared. That's why I say I didn't have a good time (in the 1970s). I had a nice record out and they didn't promote it.

CAD:

What else did you do in the 1970s?

AZ:

Let me see. I started to go up to Vermont at the same time that I was at the Half Note.

CAD:

Where?

AZ:

Vermont. I'm sorry. That's my faulty language. I never learned (English), and I'm dying. Anyway, at that time I got the idea to move to Vermont. I'm a skier. I was divorced. I was in a bad way. I lost my family, my three-year-old daughter, everything, when we got divorced. I was kind of stranded in New York because they moved to St. Thomas, you know. My personal life was messed up, so I was not good, you know. That was the scene then. But I did very important things in those days because I set up the Vermont Jazz Center. I didn't know how it was going to come out. I tell them I'm going to do some teaching there and put some concerts on. But the idea came a little later when I saw that in Vermont actually there was nothing (regarding Jazz). We were in one of the three United States "survival sites": Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine. (Laughs) There was no Jazz at all! I thought, "That's impossible. We'll do something about that." So I started to put some concerts on at the local nightclub. It was like a restaurant: the Mole's Eye Cafe. It was down in the cellar.

CAD:

Did anyone come to join you from New York?

AZ:

Oh, yes! Oh, yeah. I mean, I tried to engage everybody that I knew. Like George Mraz

is also a ski nut. He likes to ski. He came up first here, and then some others came, like

Claire Arenius. That was the first trio that played there in Vermont with George and Claire. And then I got Fred Hersch; he played one weekend. He played there with

George Mraz and me. We played in a trio; I have a tape of us. Every weekend, I played with one or another there. I tried to make the people come to the restaurant. We played first for 20 people.

CAD:

Did you keep your home in New York?

AZ:

Yes. I just bought a house to get away from the scene there and just relax out there. And then when I saw the potential, I expected I'd need a house. It just was a camp, actually, with no basement. And I built it into a huge mansion. After a few years, of course, I lost it. I couldn't keep up the mortgage. My home there now is on the same land. I just sold part of the land with the house and built another house.

CAD:

What else happened to you in the 1980s? CAD:

What else happened to you in the 1980s?

AZ:

It wasn't like the '70s. It was much better. Ah man, there were students and the school that we began. Already, in one year from '81 and '82, three students came up nice, you know. And the teachers had the work, you know. We had very good support. I have a whole list of who was there - Lee Konitz,

Roland Hanna and a lot of people. But the Vermont Jazz Center is known already. Another recording that I did in 1980 involved a solo album named

Conjunction (1979) on Enja Records. Two of my other Enja albums came out on CD recently,

Overcome and

Common Cause. The 1980s went uphill for me.

CAD:

Did you stay in Vermont in the 1980s?

AZ:

Ya. In the 80s then, things started to grow already with the money, and I worked. And then I got to be really big. I started thinking to myself that I didn't have to live in New York to do my jobs in Europe. You see, in Europe I am in a different - how do you call it? - environment. The people think differently about me in Europe than they do here. Over there, you are an artist; here, you are a musician.

CAD:

Do you have more of a following in Europe? CAD:

Do you have more of a following in Europe?

AZ:

Oh, yeah. I don't know about the numbers. I am in the (European) promoter's eye. I didn't disappear. What I am doing on guitar is not ignored there; here, it is ignored. That's why I tried to play something popular then. In my forty years here (in New York), I have learned something. I am not just for business here, you know. I am not at all for business. I am just for music here and I wanted to find out how it works, and that was nice. There are different aspects that I learned here - different motifs, different ways of playing Jazz. But I have only artistic ambitions and not financial ambitions.

CAD:

Has it been hard for you to make a living?

AZ:

No! I don't like making certain types of music just for the money's sake. That is an "in" thing to make a hit. I like to do some original stuff that people like. And if they like it, I like it too. I like when other people like it, but I don't care if they don't like it when I play in certain places the wrong (popular) music. If it's not my music, I'd rather not play that any more. Anyway, that is the problem: to make financially also a good living with music. But you play the right music for the people, right? But if you feel it's not what the people want to hear, that is no good. That's how it works. I don't complain. I don't have the least reason to complain. I'm seventy. I was almost seventy when I made my solo album. On June thirteenth (1997), I was seventy.

CAD:

You're playing as well as ever.

AZ:

I'm playing better! I tell you, I'm not trying to sell anything. I talked to Tommy Flanagan and he's making an album now. He said, "I want to do a standards album now because I never sounded so good before."

CAD:

Could you tell me about your guitar inventions, like the bi-directional pick-up?

AZ:

It involved a lot of research for sounds. Every pick-up looks almost the same inside, you know. The difference is also important - where everything is and how it's laid down and how it's built. I mean, there has to be a solid piece on the end. All kinds of things. The pickup has a flat sound; you can do anything you want with it. It's a flex response pickup. For example, if you want a different sound, you would do the orchestra way, which I discovered. But you don't have to discover all of that to make a pick-up.

CAD:

Have you designed electronic instruments too?

AZ:

No, I have no knowledge about electronics. I made the first pick-up also for vibraphone for Gary Burton. I did the work with him. He bought a pick-up. Shortly after that, somebody else came out with a better pick-up. It was easier to work with. With the electronic part, they saw what I did and said, "Oh, if it works like that, then it could work this way too." They tried it; it worked. The pick-ups are direct for the notes in that each note is a wire coming out. They can do that now because they know that aluminum is a magnet. The aluminum notes are responding to magnetism. So that's what I did - a difference in the pick-up. I found a pick-up factory in Germany who would do this:

Shadow Electronics. They produced then that AZ-48 Design. It was called "48" because I was 48 years old at that time. I wanted to make the electronics easy.

CAD:

I see that you were honored at the American Guitar Museum.

AZ:

Oh yes. There were 50 guitar players there, such as Jim Hall, Peter Bernstein,

Abercrombie and Scofield. (Laughs) There was about every guitar player over there; it was like a convention, you know. And of course, a lot of the younger cats were there -

Russell Malone. That was for me as a guitar player, of course. The fellow put it on there, because I'm sick, to cheer me up or something. It was a surprise party; I didn't know. He said I could try nice, expensive guitars - $50,000 guitars. I thought, "I ought to try that!" So when I went there, there was only one guitar there. I thought, "What is this? This is the wrong place." I thought it was a chance to try the guitars. I thought I could take them down and play them. Anyway, it was a big surprise. Even Herbie Mann was there. (Laughs) Joe Lovano was there - lots of musicians.

CAD:

Have you been sick?

AZ:

Yes, I'm full of morphine. A little too much, you know. (Laughs) I have colon cancer, yes. It's down in the fourth stage already. I'm losing weight. You know, you'll have to excuse my language because I am now feeling that I am drunk or something. So that just makes me kind of drowsy and like I'm drunk, you know. I'm still full of engagements. Like tomorrow I have a concert to play at. I don't know yet if I'll make it or not; I'm trying to make my mind up. Up until 1990 to 1992, things were very good with steady growth. Then in '94, I had a gall bladder operation, and the whole mess started.

CAD:

Did they find out you had cancer then? CAD:

Did they find out you had cancer then?

AZ:

No. At that time it was just my gall bladder. I shouldn't have done it. I did it, and then a year later, I got the diagnosis with cancer in November. Then they made the operation. In '94, I had a record named for the doctor. It was called

When It's Time

(Enja). That's what I said: "When it's time. Don't worry. You don't think I'll die now. When it's time!" It's a beautiful ballad on that record.

CAD:

You recorded with Jimmy Raney (L&R Records) in the early 1980s.

AZ:

We made two records. One was made in '79, and two records were made in 1980 because there were both concerts. One was in a big concert hall - the

Jahrhundert Halle, or the Century Hall - with 2000 people in Frankfurt. It was a big festival, and one concert featured three spontaneous improvisations over themes with no pre-arranged playing. It's not so easy. We recorded it, and it came out. It's going to be an album for the next fifty years, you know. It was very good; we played with a symphony. Anyway, we made two records from that with

Jimmy Raney called Jim and I because all of the three LP's came out on one double-CD. Then

Common Cause is already on two other records - on the end of Conjunction and the end of the album

Common Cause. The end is two pieces of the solo. After that, I had nothing else but the new Enja record, which is

When It's Time with Lee Konitz,

Larry Willis, Yoron Israel and Santi Debriano. Also, I did

Thingin (HatArt) with Lee together, which became noticed. It already had good reviews. It was the record of the month in Germany. It is almost uncategorized. It is very special, very good music. I mean, before I go, with that album, it's nice to know that something is cooking.

January 9, 1998 - Jackson Heights, NY

Attila Zoller died on January 25, 1998

in Townshend, VT.

(copyright) ©1999 Cadence Magazine

Cadence Building, Redwood, NY 13679 USA

ph: 315-287-2852 fax: 315-287-2860

email: cadence@cadencebuilding.com

website: www.cadencebuilding.com

Postscript By Eugene Uman

Until the last year of his life when cancer slowed him, Attila Zoller swam back and forth five or six times a day along a long concrete dam which briefly confines the West River into a small lake called Townshend Lake. The lake is in the small town of Townshend, Vermont, about eight miles from Attila's rustic home in Newfane, Vermont. Below this dam, the West River curls southeast, hugged by Vermont Route 30, until it arrives in Brattleboro, where it feeds into the Great Connecticut River. From there, the crystal clean waters of Vermont run through Massachusetts, Connecticut and New York into the Atlantic Ocean.

So too have traveled some of the remains of Attila Zoller.

Attila requested that his ashes be distributed into the waters of this peaceful place where he felt close to nature. Attila told me that he didn't like the idea of a gravestone where people would come to visit "somebody's old bones." Now people can remember Attila when they swim in his favorite place.

On the frigid morning of January 28, Attila's daughter, Alicia Zoller; Attila's "love of his life," Joy Wallens-Penford; Attila's good friend and confidant, Terry Solaro; Attila's long-time friend, musical associate and vice president of the Vermont Jazz Center, Howard Brofsky; and Attila's new friend and newly appointed director of the Vermont Jazz Center, Eugene Uman, gathered at the snow-covered dam.

All of us realized that the ice was too thick for chipping away a hole to spread Attila's ashes. So we all looked around and saw, about 300 yards to the south, an old abandoned covered bridge, the longest single-span covered bridge in the entire state. The West River ran quickly and freely below it. The bridge was the perfect place from which to spread the ashes of the man we all cared for so completely.

We parked our cars on the side of Route 30, and in a bittersweet celebration we opened a bottle of champagne and toasted Attila, friendship, love, the Vermont Jazz Center, and of course music. We drank the champagne from paper cups and then used those very cups to toss Attila's ashes into the shallow running waters below. Alicia started and we followed, muttering our little prayers and knowing that this was a monumental occasion, but feeling naked during a moment of such import.

If one looks closely, a person can find, carved into

the bridge, a guitar initialed "AZ" next to an arrow pointing into the

glistening water.

|

Insert a comment

©

2000 - 2004 Jazzitalia.net - Cadence Jazz Magazine - All Rights reserved

|

© 2000 - 2026 All the material published on Jazzitalia is exclusively owned by the author. Moreover it is protected by International Copyright, so it is forbidden any use of it which isn't authorised by the rights' owner.

|

| COMMENTS | Inserited on 13/2/2009 at 21.14.16 by "jonhammond"

Comment:

Excellent Attila Zoller interview! I'm sorry that Attila was a little bit cranky to the interviewer, he was a nice guy, I am Jon Hammond the organist who played with Attila when I was living in Germany.

Here is a film of us playing in Frankfurt 1994 at the Jazz Kneipe: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=slC9yIBJ6m4

Attila Zoller and Jon Hammond Band Jazz Kneipe Frankfurt: Attila Cornelius Zoller (June 13, 1927 Hungary - January 25 1998 Vermont) famous Hungarian Gypsy Jazz Guitarist with Jon Hammond Band

at Jazz Kneipe Frankfurt playing Henry Mancini composition "Days of Wine and Roses", Attila Zoller guitar, Sergeant Al Wittig U.S. Air Force Kaiserslautern

tenor sax, James Preston of Sons of Champlin drums and Jon Hammond at Hammond XB-2 Organ.

Keep up the great work and keep the Spirit!

Sincerely,

Jon Hammond (today in Seoul Korea)

*Member American Federation of Musicians Union Local 802, Local 6

http://www.jonhammondband.com

| | |

This page has 9.926 hits

Publishing Date: 06/01/2005

|

|