Written by Jim Eigo:

jim@jazzpromoservices.com

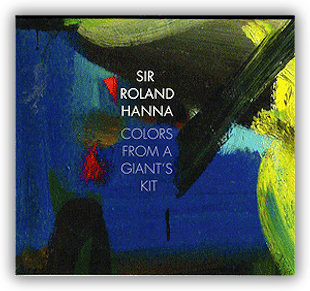

Sir Roland Hanna

Colors From A Giants Kit

IPOCD 1020

Street Date August 9, 2011

The Hickory House was the last of the legendary jazz clubs

that lined 52nd Street in the two decades following World War II. In the mid-1960s

the bandstand, which rose above the large, horseshoe-shaped bar that dominated the

club, was occupied as often as not by a trio comprised of Billy Taylor,

Chris White and Grady Tate. The club was still patronized by some

of the musicians who immortalized the street in the previous decades, and for the

odd 15-year-old whose interests ran more to Dameron than trigonometry, it was a

place to hang out and an opportunity to meet (or at least interrupt the otherwise

tranquil dinners being enjoyed by) Ella Fitzgerald, Milt Jackson and

others who dropped by.

The trio typically closed its sets with a rollicking version of There Will Never

Be Another You or How High The Moon that included an expansive, unaccompanied,

two-fisted, polyphonic piano solo by Dr. Taylor. Carding was not a problem

at the Hickory House and, carried away by such a tour de force performance, it would

not be surprising had any of those odd 15 year olds who happened to be in the club

decided to become a jazz pianist. Fortunately, Chris White was there to commemorate

the event and to recommend his colleague in the Dizzy Gillespie Quintet,

Kenny Barron, as someone who could show me the way.

Kenny was doing some teaching out of a small studio on the West Side. Relying on

chops honed by a few years of obligatory grade school piano lessons and confident

in my innate musicianship and good taste, I shared with Kenny a pastiche of bebop,

funk and random atonality that had him transfixed for about ten minutes, and left

him nearly speechless. As much enthusiasm as he obviously had for taking on a new

protégé, he felt (upon recovering his power of speech) that his commitment to an

upcoming Gillespie tour (which curiously both he and Chris White had neglected to

mention before) would make it impossible to devote the time required to nurture

such an unusual talent. He gave me Roland Hanna's number.

"I always learn something new when I play with Roland," said Benny Carter,

quoted in the liner notes to his "In the Mood for Swing" album with Roland

and Dizzy Gillespie on the Musicmasters label. Coming from Carter, an

iconic figure for over seven decades who essentially created the art of jazz band

writing, this is not a trivial statement.

Teaching played a large part in Roland's life, and he held firm opinions on music

and many other subjects. When I first met him, he had a studio on West 73rd Street,

where Broadway runs into Amsterdam Avenue, adjacent to the tiny trapezoid of grass

that now appears on maps quaintly as "Verdi Square" but at the time was known more

colorfully as "Needle Park." I used to drop in whenever I was in town visiting from

college and grad school. Roland had an ancient Steinway that he tuned and maintained

on his own. I once commented that it seemed to me the bass was disproportionately

voiced. Roland, as always justifiably proud of his own work and quick to the defense

of others, responded: "by the time you get to be eighty years old, your bass will

be disproportionate too."

In the mid-late ‘60s Roland had two regular gigs that would be almost impossible

to top – he held down the piano chair in the Thad Jones – Mel Lewis Jazz

Orchestra and was a regular accompanist for Coleman Hawkins. The Band

was in its prime, with Thad producing fresh and innovative charts for a roster of

players that was and still is beyond comparison. This was during one of the recurrent

nosedives in the economics of the jazz world, of which there were nonetheless a

few benefits. Players such as Joe Henderson, Pepper Adams, Eddie Daniels, Jimmy

Owens, Bob Brookmeyer, Jimmy Knepper etc. were available to be part of a regularly

performing band. On the other hand, people didn't always get paid with regularity.

I once spent some time with Mel Lewis trying to mediate a disagreement with Roland,

at a time when the Band's future was cloudy. Mel told me that, no matter what, he

would always take great pride in having been part (along with Roland and Richard

Davis) of the "best rhythm section in history."

The Jones-Lewis studio recordings don't come close to capturing Roland's importance

in the Band. More often than not, arrangements were framed out with Roland's extended

introductions and solos, and there were always uncanny exchanges between Roland

and other featured soloists. Then, there were the moments when all the other players

would silently descend from the bandstand in the middle of a set, leaving Roland

alone at the piano for seven or eight minutes of an unaccompanied improvisation

(typically as an introduction to "A Child Is Born") that embraced just about

every musical style and technique imaginable. As Roland neared conclusion, the others

would file back to their chairs and settle in for the B-flat seventh chord that

marked the transition to Thad's arrangement. It was very cool.

Like Thad Jones, Coleman Hawkins had exemplary taste in pianists. His sessions featured

some of the earliest recorded performances of Art Tatum, Bud Powell and Thelonious

Monk. Starting with Hank Jones in the 1940s, playing for "Bean" became a rite of

passage for the members of the "Detroit Piano School," including those who eventually

followed Hank to New York: Tommy Flanagan, Barry Harris and Roland Hanna. They would

often hang out at Bean's Upper West Side apartment; playing the piano for each other,

listening to records and talking. Roland let me tag along to a couple of these get-togethers,

where the subjects of conversation, as I recall, ranged from dining on pigs feet

to the defining qualities of fine classical ‘cello playing (I don't recall the segue

between those two subjects; perhaps the correct angle of the wrist). Then, in 1967,

a great aunt died and left me $5,000. I was in college, and the only thing I spent

money on was records, so I figured if this legacy were going to be converted to

vinyl in any event, I might as well bypass the middlemen and do it in style. Roland

had not at that time recorded his own compositions (which eventually grew to several

hundred works and included, in addition to jazz pieces, works for violin, ‘cello,

chamber ensemble and orchestra), so we organized a couple of sessions at the old

A&R Studios in the West ‘40s - one session with talent drawn from the Band: Thad,

Mel, Eddie Daniels and Richard Davis; another with Coleman Hawkins.

$5,000 obviously went a lot farther in those days, but not quite far enough, and

mistakes were made. In the interest of economy, I booked the cheapest studio time

available – with a 10:00AM start time – figuring that this wouldn't conflict with

the musicians' other engagements and would enable them to focus their full concentration

on the music, uncluttered by the intrusion of other concerns of the day. This must

have been a particular novelty for Hawkins, whom I later came to realize had probably

never before been awake at 10:00AM – or, if he had, it was most certainly at the

end rather than the beginning of his day, when his capillaries were transporting

more Hennessy than hemoglobin. I remember Roland and Eddie Locke carrying Bean into

the studio and positioning him in front of the music stand. This held a composition

that Roland had written for him called "After Paris," an evocative impressionist

piece formally notated with a maze of accidentals and double sharps. I still can't

imagine what the double sharps looked like to Hawkins under those circumstances,

and in truth we couldn't salvage much from the session, except an indelible memory

of the majestically beautiful tone he still produced.

Lacking further windfalls, it took another 35 years before the IPO label came into

existence, initially with a solo album of Roland called "Everything I Love" and

a set of Arlen tunes with Roland and Carrie Smith, "I've Got a Right to Sing the

Blues." In between, anticipating at one time or another the start of the label,

we recorded on a couple of occasions that produced the material included in this

release. It took longer than expected for IPO to be up and running, and then it

took a while to go through the old master tapes, and then Roland wasn't around to

approve the final selections and order of the pieces, and …well, the point is that,

notwithstanding the lateness of their release, these performances are masterful,

top-of-the-barrel, premier cru Roland Hanna, maybe even the best he ever recorded.

When Roland died in 2003, Stuart Isacoff, editor of Piano Today and an old

student of Roland's, wrote an article in his magazine reflecting on their long friendship.

"I wanted to make him proud, and still do," Stuart wrote. Learning from Roland

Hanna, being inspired by him, and having him as a close friend for all those years

was an experience for which I'm immensely grateful. And, I'm sure he would be proud

of this recording.

Bill Sorin

January 2011

Label Website:

www.iporecordings.com/

Distributor Website:

http://www.allegro-music.com/

National Publicity Campaign Media Contact:

Jim Eigo Jazz Promo Services T: 845-986-1677 E-Mail:

jazzpromo@earthlink.net

http://www.jazzpromoservices.com/

National Radio Promotion Contact:

Mike Hurzon

The Tracking Station

476 NE 2nd Avenue

Fort Lauderdale, FL 33301

trackst@bellsouth.net

(954) 463.3518

|